"A perfume of delicious wickedness pervaded the atmosphere." Francis Schneider, Manet's biographer

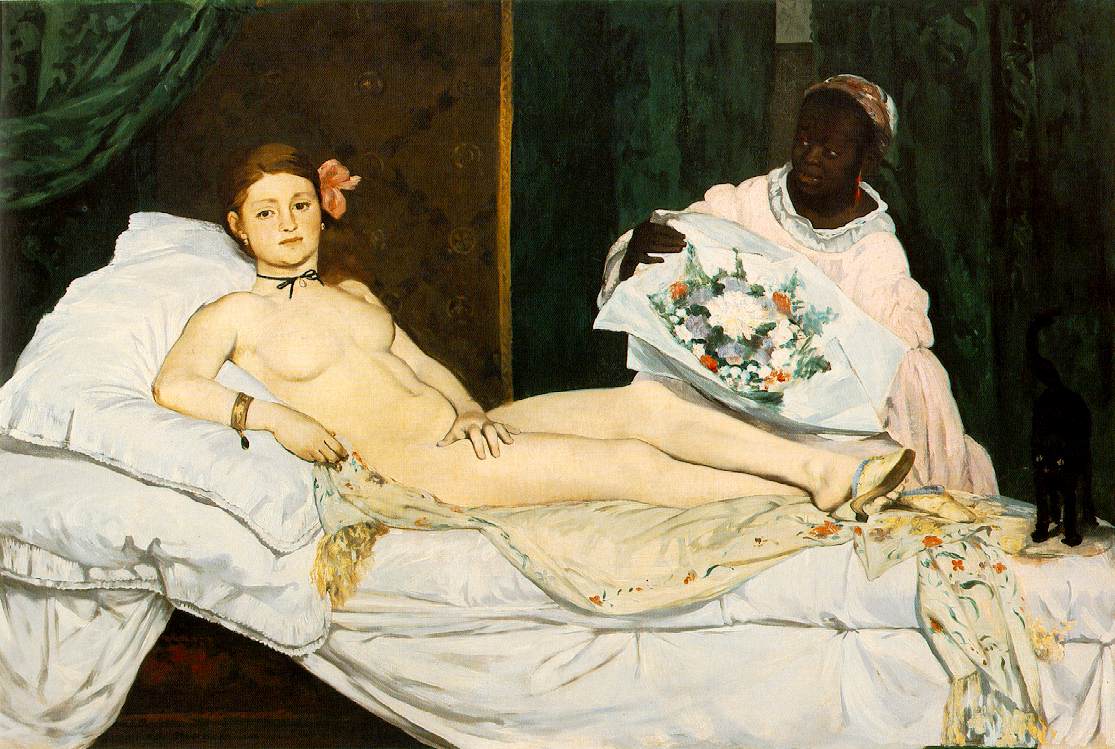

Manet's Olympia lies atop her unmade bed, reclining on over-sized pillows. Her black cat rests at her feet. Her black servant has brought in a fresh bouquet of flowers, a gift from a previous admirer. Olympia flaunts her nudity. She wears nothing in her Montmartre apartment, save for her slippers, a bracelet, a black ribbon around her neck and the symbolic orchid in her hair. She is no perfect woman, but she does glow in her confidence, dangerously bordering upon conceit. The flowers do not impress her, they only feed her dominant appetite. But then the door to this scene is opened unexpectedly, and there you stand. An early, intimate intruder. Take in the scene and the intimate scent that lingers above the fresh flowers, themselves both a trophy and a challenge. The black cat is alarmed. Olympia is not. She casts her gaze directly at you. She confronts and challenges you with her dark eyes. Well, this is what you came here for, isn't it?

Scandal, shock and horror! Manet painted Olympia in 1863 and showed it in the Paris Salon of 1865. Surrounded by the acceptable nudes adorning the halls of Louvre. Olympia did not belong there! But where did this outrage eminate from? Certainly, the painted female nude was nothing new to the French bourgeouisie who attended the salons. However, everyone was used to the "academic" nude. Beautiful, idealized goddesses, who posessed two key virtues - perfection and modesty. But Olympia was no beautiful, idealized woman. She was real. And she was clearly a prostitute. Three strikes.

Edouard Manet was born to aristocratic and political parents in 1832, and died of untreated syphlis in 1883. In between those 51 years, against his parents' wishes, he devoted himself to art. He is credited with being the link between Realism and Impressionism and for ushering in the dawn of modern art. In his twenties he travelled around Europe, studying and sketching the masterpieces he encountered. One such materpiece must have engrained itself deep into the psyche and sketchbooks of Manet - Titian's Venus of Urbino, which is hanging in the Uffizi in Florence.

"Olympia" is a name that reminds us of mythology. Of Mount Olympus. Of gods and goddesses. It was most certainly acceptable to paint female nudes, so long as they were goddesses - coy and demure. Those adjectives describe Titian's Venus well. Her head tilts to the side and her eyes meet yours from her soft, reclining angle. Her left hand ever so delicately hides her vulva from view. Her skin tones are modeled to perfection. Her hair is the high Renaissance ideal.

"Olympia" is a name that reminded 19th century Paris of prostitution. It was a common name for these women at the time. Manet's Olympia is no goddess. She lays on her busy bed, receiving a floral gift from a prior client. And you are the next one, only you have arrived a bit too early. Olympia half-rises to meet your gaze directly with her challenging stare. Manet paints the orchid, another symbol of Parisian prostitution, in her hair. She is naked, save for a small black ribbon tied around her neck, a bracelet on her wrist, and one slipper dangling off of her feet. Her pose is directly descended from Titian's work. However, there are clear and bold breaks with the the Renaissance Olympia in Manet's work. The new Olympia is staring straight ahead, gone is the coy turning of the head to the side. The new Olympia is not a perfect woman. There seems to be an asymmetry of the eyes. Her skin is white. Too white. Manet has omitted the depth of modeling in the skin that Titian crafted. Manet's Olympia, too, holds her left hand over her vulva. However, she is not slightly hiding her genitals. She is forcefully defending them from your sight; a symbol of the new Olympia's sexual independence.

Manet's painting does indeed manage to capture a distinct aroma of delicious wickedness. And sexuality. Those aromas are absent from the Titian painting, and all of the state-accepted academic art of the time. Manet, influenced of course by the masters, most successfully brings the classic woman out of the past and into the modern world. We have no goddesses here, Manet declares. Feast your eyes upon your new muse, gentlemen. She captivates in the ways those mythic nymphs never could.